Sp7 — A Photo Oxford Retrospective

OXFORD | In its 10th year, the U.K. photography festival investigates archival history with "The Hidden Power of the Archive"

WORDS BY RACHEL SEAH

Collectively, we take our starting point from archives, which allow us to gather ideas from the past in order to reconfigure the future. And in the past decade, technology has proven itself to be capable of collating and digesting these archives. With the advent of chatbots like ChatGPT doing the researching, thinking, writing, and emoting for us, I wonder where that leaves us in our design ideation. Upon the announcement of the theme across the city of Oxford’s Photo Oxford 2023 photography festival — The Hidden Power of the Archive — I sought to understand how contemporary photographers use different facets of archives to inform their new installations, and how these facets help gather people together.

Alex Schneideman, Artistic Director of the festival, details in the festival programme how they are engaging the vehicle of the archive “to examine photography from its beginnings to contemporary discussions around race, identity, sexuality and what it means to belong.” This festival looks at the juxtaposition of historic archives with contemporary works, and examines the transformative influence of archives on the medium as it exists today.

NOTHING BEATS THE REAL THING

Starting the day at the Bodleian Library, I headed straight to the pop-up library tucked in the far-left corner of the building. A temporary pop-up library curated by photographers Philippa James, Emma Davies, and Rolf Kraehenbuehl, the library titled Women and the Photobook showcases wide-ranging photographic books created by women. Said to have been inspired by a “book on photobooks'' anthology, titled What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999, this library uses the corporeality of both past and new photobooks as archives to expose the unseen and under-recognised titles as works of value. To show appreciation for the perspectives and approaches that women have paved in the art of photography, Women and the Photobook re-enacts the physical act and notion of visiting a library, where one can unravel the mystery of their book of interest alongside fellow strangers.

With ecological impact as the key concern for sustainable photobook publishing, in due time, physical books might be harder to come by than we think. The curators have made it a point to continue touring Women and the Photobook at photography festivals and women’s events. And whilst physical books might be going out of style, it seems a worthy cause to remember the overlooked voices of hidden figures who’d been shelved away, only to be revived to finally serve their intended purpose in this pop-up library.

SPECULATIVE AND IMAGINARY

Walking down Woodstock Road, I stopped at the Carey Blyth Gallery to catch Anne Howeson’s Feet of Angels. In her new body of work, Howeson responds to early photographs taken by William Henry Fox Talbot, overlaying original landscapes of industrialisation with modern and surreal additions. She explains her fascination with Fox Talbot photographs as one that is strange, yet intimate and alive. Working with digital prints as the base and using gouache and conte to layer on top of the replica digital print, her amalgamated sketch reflects on the historical and contemporary, underscoring realities with aspirations for a peaceful existence.

I was particularly drawn to the work titled Burning Books, which reflects a perturbing scene of St. Pancras Railway Station. Howeson added officer figures watching the burning of books — probably a reference to the Nazi book burnings campaign in the 1930s — with planted trees growing behind them. I admire the way she manifests her imagination beyond reality and into the ethereal dimension. In her works, Howeson balances tragedy with hope, allowing viewers to see a through-road out of any situation.

SITES OF EMPOWERMENT

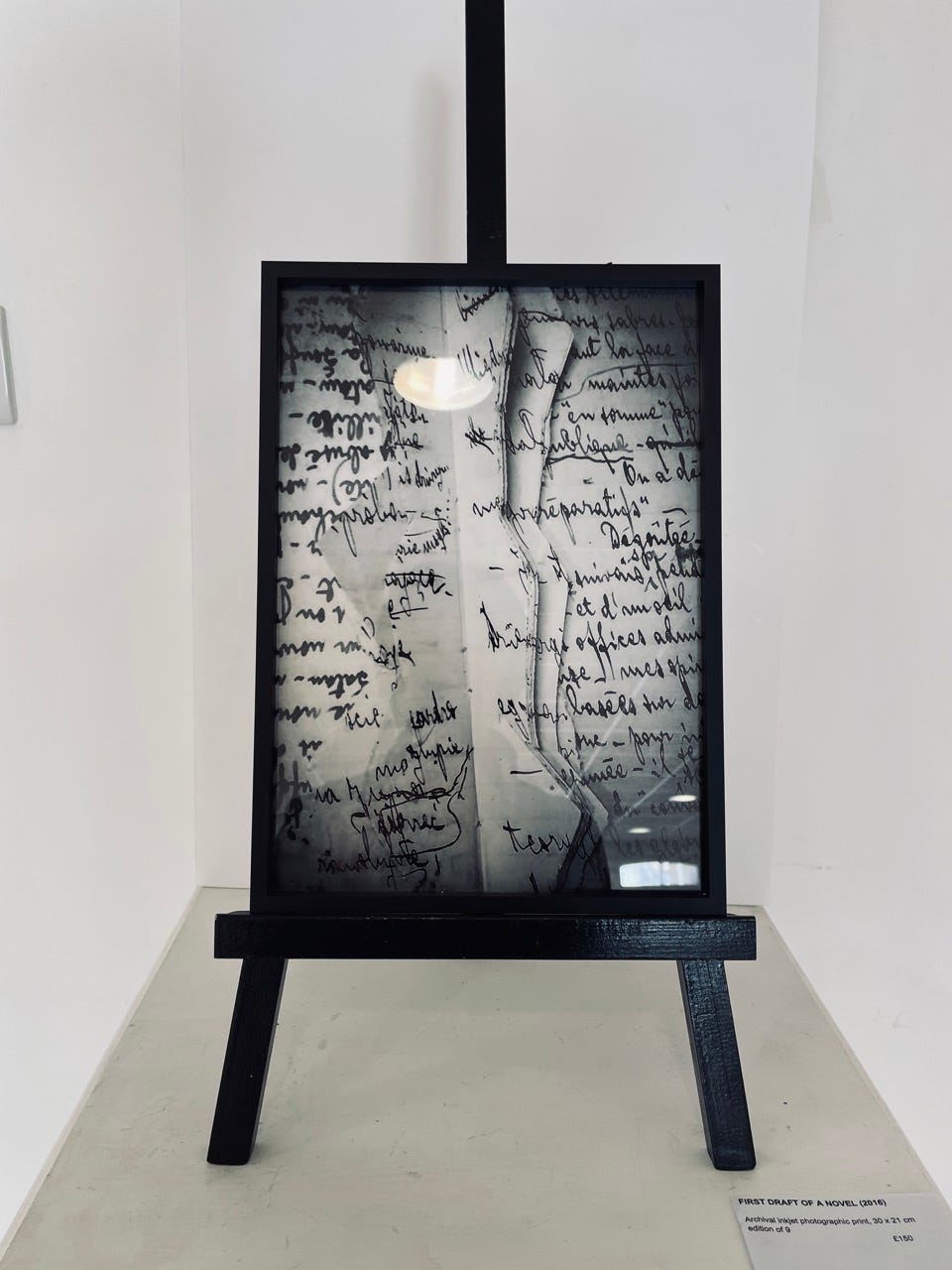

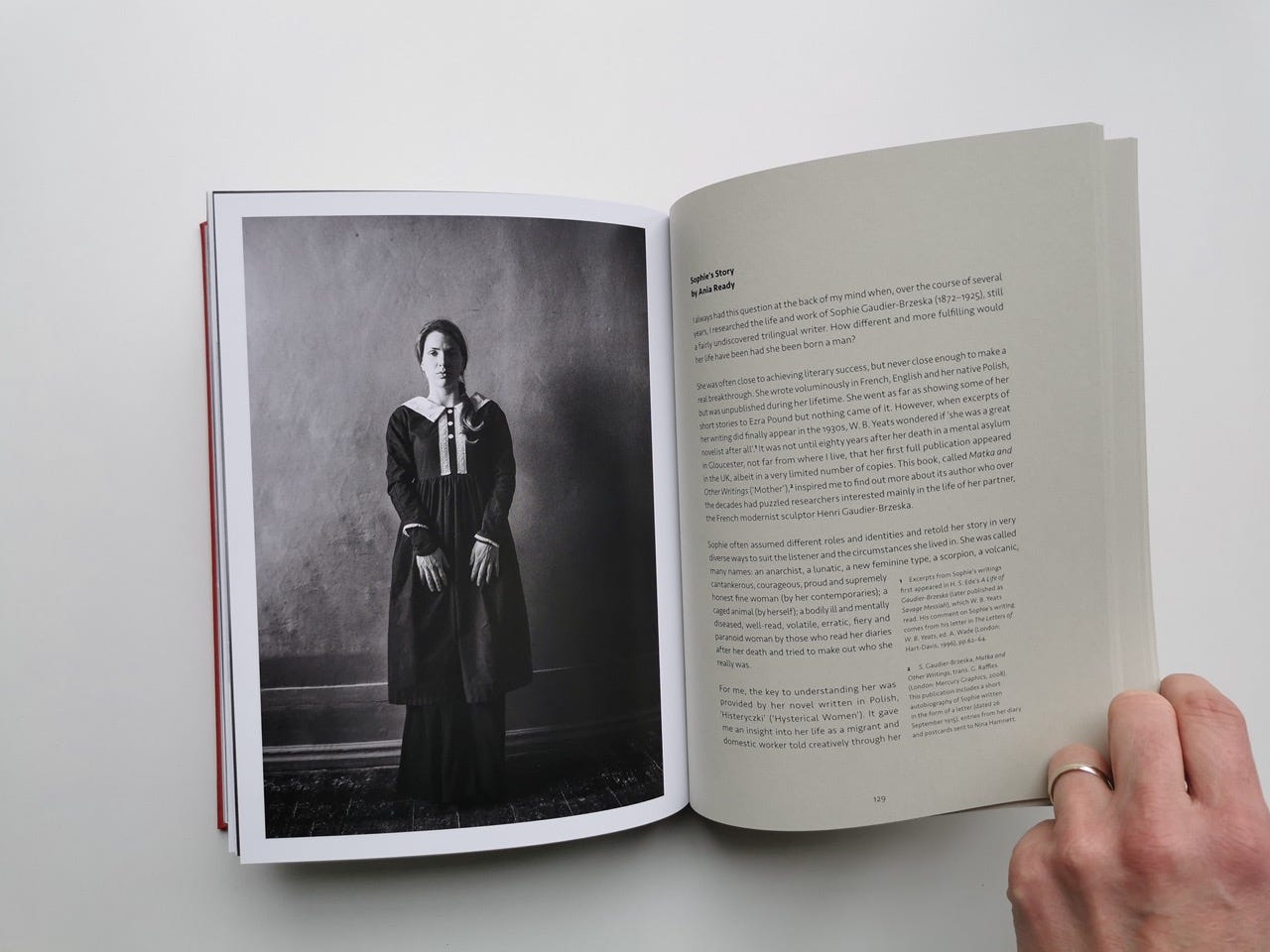

I next moved to Walton Street, where Polish-British artist Ania Ready’s I Also Fight Windmills was on display. Ready explores the challenges of the old societal order, one that prevented the emancipation of women, as if they are her own. As a visual response to the literary archive of the feminist writer Sophie Gaudier-Brzeska, she reimagines a story of a migrant woman from Eastern Europe who boldly ventured to the West in hopes of seeking employment, with the ultimate goal of becoming a writer.

With the photographs framed as though a window to one’s room, Ready invites viewers to peek into a life of displacement, loss, creativity, loneliness, a disempowering sense of guilt, and social exclusion. Ready, in her essay published in the photobook, asks: “How different and more fulfilling would her life have been had she been born a man?”

ALL IN THE COMMUNITY

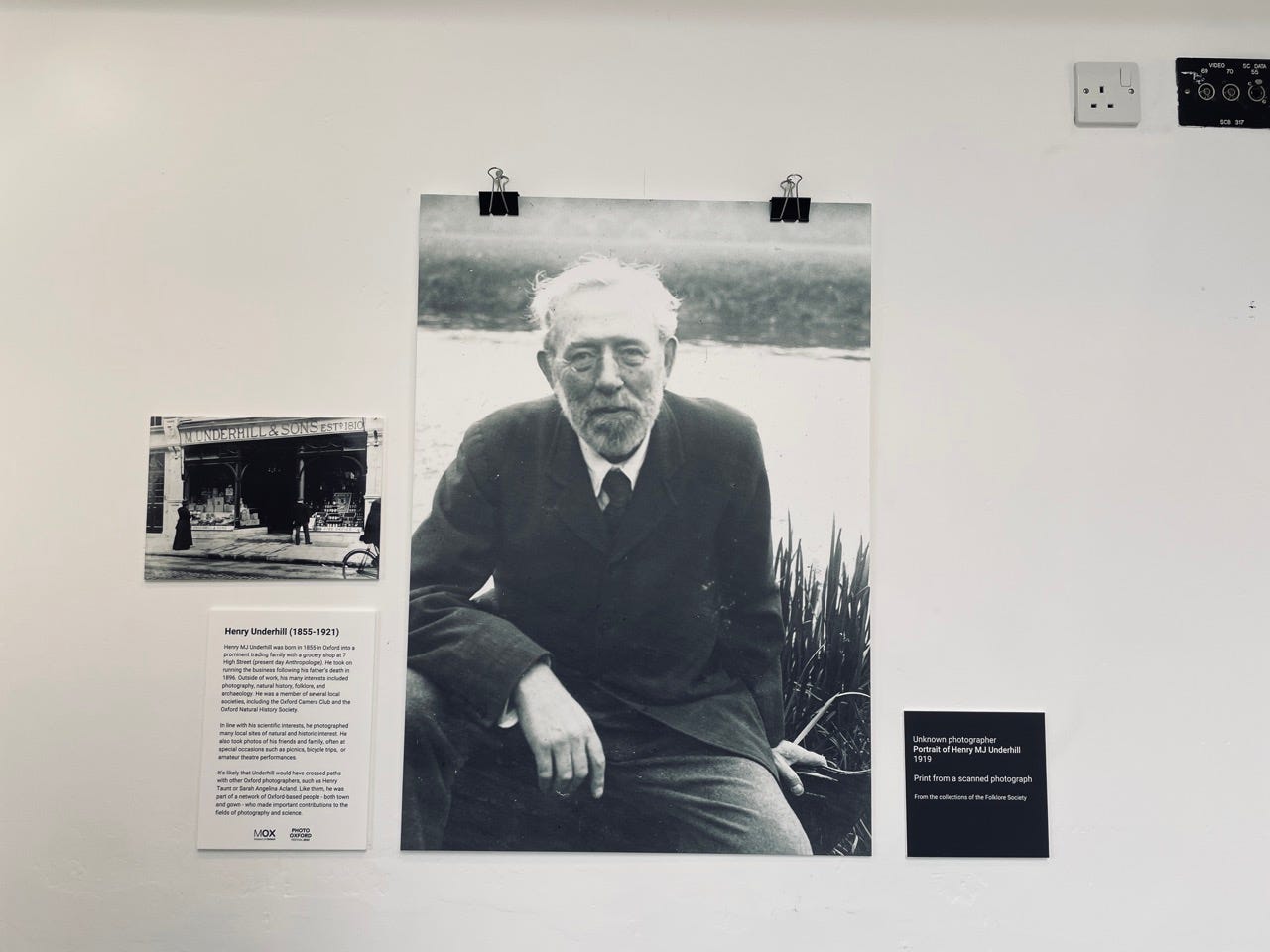

Arriving at an unassuming theatre, at first I wondered if I had mistaken the address for another location. I soon found my way up to the café of the Pegasus Theatre, where I was greeted by chip-shop owner and photographer Kazem Hakimi. The Oxford-based photographer runs a well-loved chip shop on Iffley Road and takes candid pictures of his customers as their food cooks. With a setup of a white wall at the back of his chip shop and only natural lighting, Hakimi takes quick and informal photos of his customers. Alongside his portraits were portraits taken by Henry Underhill, a grocer and photographer in the 1900s, who took striking portraits of his friends and family in their moments of leisure.

The exhibition, titled Portraits from Oxford – Archives Old and New, surveys portraits of Oxford citizens taken a century apart, with the colour of the photographic medium and period differences serving as distinguishing factors. With many of the attendees doubling as his customers, Hakimi struck me as a character who can easily rile up a room. It was an absolute joy to hear him introduce people, and it warmed my heart to witness the heart of the community bringing people together, even a century on.

NEVER OUT OF NOTHING

With the afternoon light growing duller, Hakimi and friends brought me over to Magdalen Road, where Magdalen Art Space is located. The evening marked the opening launch of LATENT: From Our Archives, where 11 studio artists explore the latent power of archives, activated and transformed through making art. Across the room, the artists covered themes surrounding the embracement of family, language, landscape, disability, and secrets in varied mediums. Each artist drew on archival found objects or memories to release and reveal their latent capacity. For instance, artists and sisters Asma Mahmud Hashmi and Peejo Sehr, in their work titled Reflections on Ami, focus on their culture’s forgotten and concealed aspects by using photographs, words, and paper lithography. They explore memories of the bygone era and its lasting influence on multiple generations. I was fixated on the personal narratives written by Sehr where she chronicles the stories of her family members. I could relate to an excerpt on her Ami’s cooking that reads: “She never forgets if you like something that she has cooked in your honour”, this for some reason reminded me so much of home in Singapore.

Down to the left of the studio space was Jane Kelly’s Polish Objects. In this piece, she compiled burned objects found in 1970s Auschwitz, formed some drawings, and shot black and white photos to serve as a reminder of the things that belonged to the Polish people during a very dark time in their history. She explained that she had found these burned objects abandoned underneath a metal grill, likely when the SS fled from the camp in 1945. She brought home various items, including women’s buttons and a baby’s coat. She has since returned the items to the camp museum in Poland. Kelly’s mixed-media work documents found objects in a controversial and condemned part of world history, and their significance to the Polish and Jewish people. Kelly’s act of using these found objects in her works, and creating sketches of them, reiterates the traditional form of recording and archiving for identification and education purposes.

I ended off with Lissa Rodd’s Of Light and Dark, where she displays her archive of digital photographs made in February 2022. It documents first light at 7:30am from both the East and West at the same spot, to form a map. This map shows the East and West sequences, respectively, to mark the changing season, accompanied with notes made daily. The recorded archive of the changing states of nature proves to be comforting, as it marks a new beginning after a bleak wintry season. It serves as a reminder that something will eventually come out of steadfast endurance and patience.

Visiting the few pop-ups and exhibitions reminded me of Nobel laureate poet Rabindranath Tagore who remarked in his lecture on the religion of an artist: that the vision of paradise is to be seen beyond just the wealth of human experiences, “even in objects that are seemingly insignificant and unprepossessing.” He further concluded that the spirit of paradise is around us and sends forth its voice, allowing it to arrive at our inner ear, sending aspirations out into the world. Artists, photographers included, play the tantamount role of delivering their intended messages to their communities─to suggest, inspire, and induce introspection.

The myriad use and activation of archives charge us to reinvent the future as ethically as possible, and I hope we can find it within ourselves to exact sensitivity, hope, gratitude, and, importantly, community spirit in the latent archives around us.