Sp8 — A Retrospective on Myfanwy Macleod’s "The Botanist"

VANCOUVER | The Canadian multi-media artist makes her Welsh debut with a contemplation on ecological preservation

WORDS BY KAYLA MACINNIS

PHOTOGRAPHY OF THE BOTANIST EXHIBIT BY KENDRA EDEN

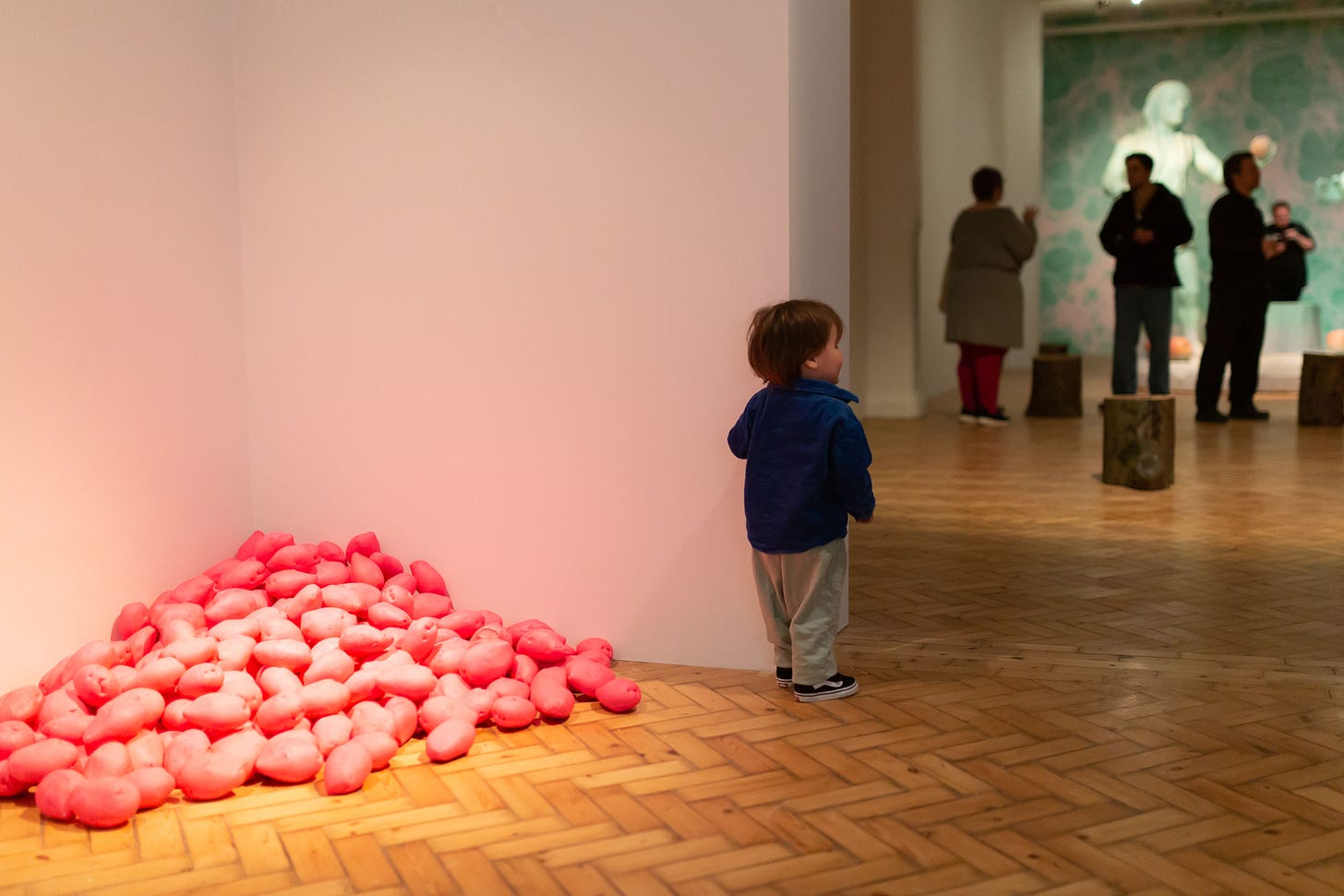

Inside Myfanwy MacLeod’s The Botanist is a question that revisits how human histories intersect with four plants: apples, tulips, cannabis, and potatoes. Interrogating the anthropocentric tendencies inherent in human existence, MacLeod traverses the capitalist and colonial structures that laid bare the dissonance between disease and preservation. The pieces reference minimalism and can sometimes feel unsettling, introducing a notion of disambiguation that draws viewers toward understanding the fundamental paradox of these relationships, and how to consider what reconstruction could look like.

Her exhibitions often touch on the complexities of past and present, national and international, permanent and temporary, all while layering references to history, culture, and folklore. Whether through sculpture, drawing, painting, photography, performance video, sound installation, or the written word, MacLeod’s denunciation and interrogation into these concepts prevent us from becoming anaesthetized to the way things are. What makes it all easier to swallow is her use of humour, satire, and allusion, which give new meaning to the things we are acquainted with every day. For example, her public art commission The Birds, explores the migration and immigration of sparrows introduced by Europeans to North America to alleviate homesickness of their “Old World.” These 18-foot-tall stainless steel sparrows invert the human relationship with invasive species, which has caused many issues for biodiversity and habitat loss, and for native species.

Born in London, Ontario, MacLeod travelled throughout Europe after high school before moving to Montréal, Quebec to study film at Concordia University. Eventually, she settled in at the University of British Columbia, where she earned her Master of Fine Arts in Visual Art and went on to teach. MacLeod’s fidelity is in respecting the land in which she resides, and as a settler, she has explored colonisation in installations such as The Butcher’s Apron, a depiction of the naval vessel captained by George Vancouver that led to the first contact between local Indigenous nations and settlers. These explorations come alive by creating a sense of juxtaposition between the manipulated and the natural, eliciting thought-provoking reactions within viewers.

CULTIVATING DISRUPTION

CAN | In The Botanist, you examine four plants (the apple, the tulip, cannabis, and the potato) as indulgent crops grown to sate human desire. What inspired this roster of plants, and how does this selection reflect your own meditations on our relationship to agricultural cultivation?

MM ─ American journalist Michael Pollan's book The Botany of Desire, which I first read in 2008, inspired my choice of plants. In his book, Pollan traces human's relationship to these four different plants throughout history as they travel from East to West and South to North, drawing the reader’s attention to capitalist and colonial structures in a process Pollan refers to as ‘domestication’. This term domestication, however, hides a multitude of sins, both past and present. As a settler of Welsh and Scottish descent living and working on the traditional unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations for the past 30 years, my understanding of the land and particularly the industrial-agricultural complex has changed enormously. The reclamation of land-based knowledge by Indigenous people, not to mention the impact of forestry and mining on the region, and how it impacts their rights and sovereignty, has influenced my own artistic practice. As Pollan points out, agricultural monocultures and the monocultures of our global economy nourish each other in crucial ways. Through my current work, I am interested in examining events, like the recent pandemic, and disorders. such as the potato disease pink rot, that have the potential to disrupt capitalism.

VIOLENT DOMESTICATION

CAN | Capitalist and colonial structures commodify time even in the creative industries, but the botanical world lives beyond the clock. How do you hope your work with these plants challenges perceptions and measurements of artistic labour and value?

MM ─ Cloning, grafting, and genetic engineering — techniques we’ve employed to domesticate plant life — are linked to 20th-century artistic movements like minimalism and modernism which similarly use acts of repetition, collage, and appropriation as part of their toolkit. As a feminist, I want to uncover the inherent violence in these acts of domestication and challenge how we have chosen to perceive and measure the world around us. The current debates around invasive species and disease and how they either affect, parallel, or disturb capitalist and colonialist value systems also interest me.

SCULPTURAL SPACE

CAN | As a Canadian artist, this is your first solo exhibition in Wales. What have you observed in regards to how the climate and plant life within this bioregion informs and inspires its creative community?

MM ─ Artists Heather Peak and Ivan Morison’s mission to create a kinship between art and nature is particularly impressive. They have stewardship of a forest on their land in Eryri, where they are working to restore native species to the North Atlantic oak forest, or Celtic Rainforest. By replacing grand fir, hemlock, and Douglas fir planted in the 1950s, and using the timber from these non-native trees to create artworks, they show how sculptural space can also be an ecological experience.